Art

December 4, 2023

La Comedia Ranchera vs The Western

Weekly on Tuesday nights at MCA Denver at the Holiday Theater Cinema Azteca, our Spanish-language film series, presents a diverse perspective of work on the traditions and modern story-telling of Latinx and Indigenous peoples of the Americas.

For this round of Cinema Azteca, Ana Segovia, one of the exhibiting artists in our current exhibition Cowboy, and writer Mariel Vela looked closely at motion pictures from the Golden Age of Mexican cinema and Hollywood Western adaptations from the 1940s and 1950s, examining their influence in shaping identities of the Charro, the Cowboy, and gender roles.

Mariel and Ana wrote the following essay discussing the focus behind their selected films.

La Comedia Ranchera vs The Western

by Ana Segovia & Mariel Vela

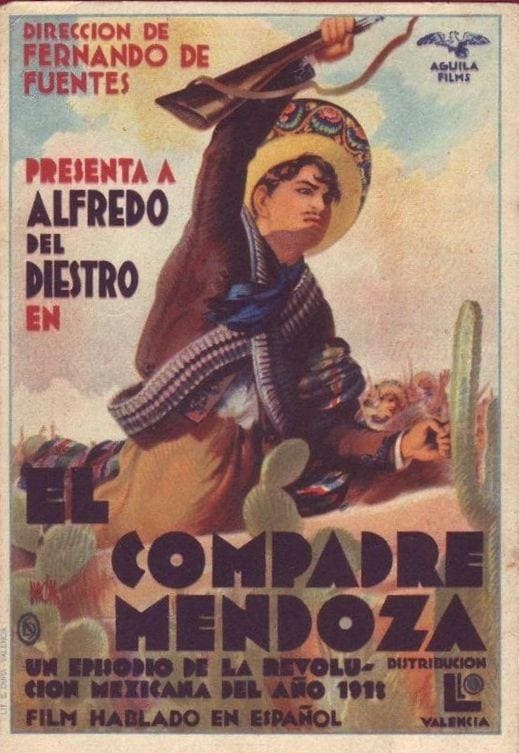

image: El Compadre Mendoza (1934). Poster courtesy of Diana Films.

From the late 1930s well into the late 1950s, a cultural phenomenon emerged across borders: the resurrection of the Western genre in the US and the birth of what we argue was its twin genre, la comedia ranchera, in Mexico. These two potent and popular genres in their respective countries would go on to become wildly popular worldwide, essentially "exporting" a synthesized vision of what these two countries represented in the eyes of their creators and history tellers. This achievement was made possible, in no small part, due to the invention of subtitles, providing the world at large with a window into how these two countries imagined themselves and their histories.

La comedia ranchera was born with the adaptation of Antonio Guzman Aguila melodramatic novel Cruz into a film titled, Allá en el Rancho Grande (1936) by Fernando De Fuentes. Regarding the film and the genre as a whole, Marína Díaz López writes in her book, Allá en el Rancho Grande: La Configuración de un Género Nacional en el Cine Mexicano:

The box office phenomenon that the film represented is part of a period of reflection on national identity in Mexico, comparable to the one that occurred at the end of the 18th century coinciding with the establishment of independent states. With the normalization of the post-revolutionary Republic, nationalism will enhance and update itself to disseminate a clear and distinct image and identity of Mexicans, giving rise to a series of stereotypes that will synthesize this intention. The peculiarity of this trend of establishing the national image is that it permeated all strata of the national culture.

Here, Díaz points out how this genre was, in many ways (we’ll argue), still deeply powerful. It cemented in its audience a set of values that would dictate what it meant to be Mexican. Keeping an eye on how this identity was performed, quite literally, we'd like to highlight how gender, race, and class have been depicted here too. “Ranchero” masculinity has been constructed in a way that is inextricably tied to a sense of nationalism in almost all of the films selected. Yes, they are stereotypes, as Díaz points out, yet the stereotype becomes real once it not only exalts existing attitudes towards women and indigenous peoples but also by creating a culture that supports and glorifies said attitudes. To be a "real man," the genre dictates one must embody and perform these values.

image: Allá en el Rancho Grande (1936). Poster courtesy of Diana Films.

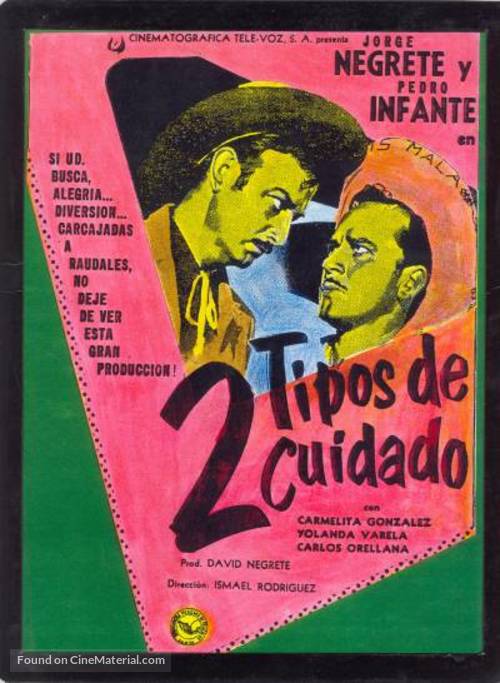

What made la comedia ranchera so appealing to its audiences were its heroes: Jorge Negrete and Pedro Infante. They are charismatic, can sing and ride horses like the two boss charros they often represent. They became the personification of Mexican stardom and the epitome of what it meant to be a real Mexican Man. Throughout the film series, glimpses of their actual personalities will shine through. They often portrayed themselves as their celebrity dictated, creating a meta-fiction of themselves on screen. In Dos Tipos de Cuidado (1953) by Ismael Rodríguez, Jorge Negrete plays Jorge Bueno and Pedro Infante plays Pedro Malo, an allusion to both their offscreen reputations and personalities. Negrete was thought of as the "good guy," and Infante as the "bad boy" of Mexican cinema. All in good fun, yet here it is clear how the very stereotypes they represented on-screen got carried off-screen, giving even more credence to the idea that these identities were not only "real" as opposed to a romanticized version of ranchero life but ought to be sought after.

image: Dos Tipos de Cidado (1953). Poster courtesy of Diana Films.

Like their Mexican counterparts, John Wayne also took much of his on-screen persona off the set and into life. The image of Wayne in our imaginaries seems static: that of a cowboy, perpetually moving westwards onto his destiny, dodging bullets and crossing rivers with a sexy smile and perhaps a cigarette dangling off of it. Like la comedia ranchera, the western genre’s formulaic and simplistic narratives rely on their superstars to hold their audience captive. When we think of the Hollywood version of the cowboy, it's impossible not to think of John Wayne and later Clint Eastwood, who would come to usurp the former with the advent of spaghetti westerns.

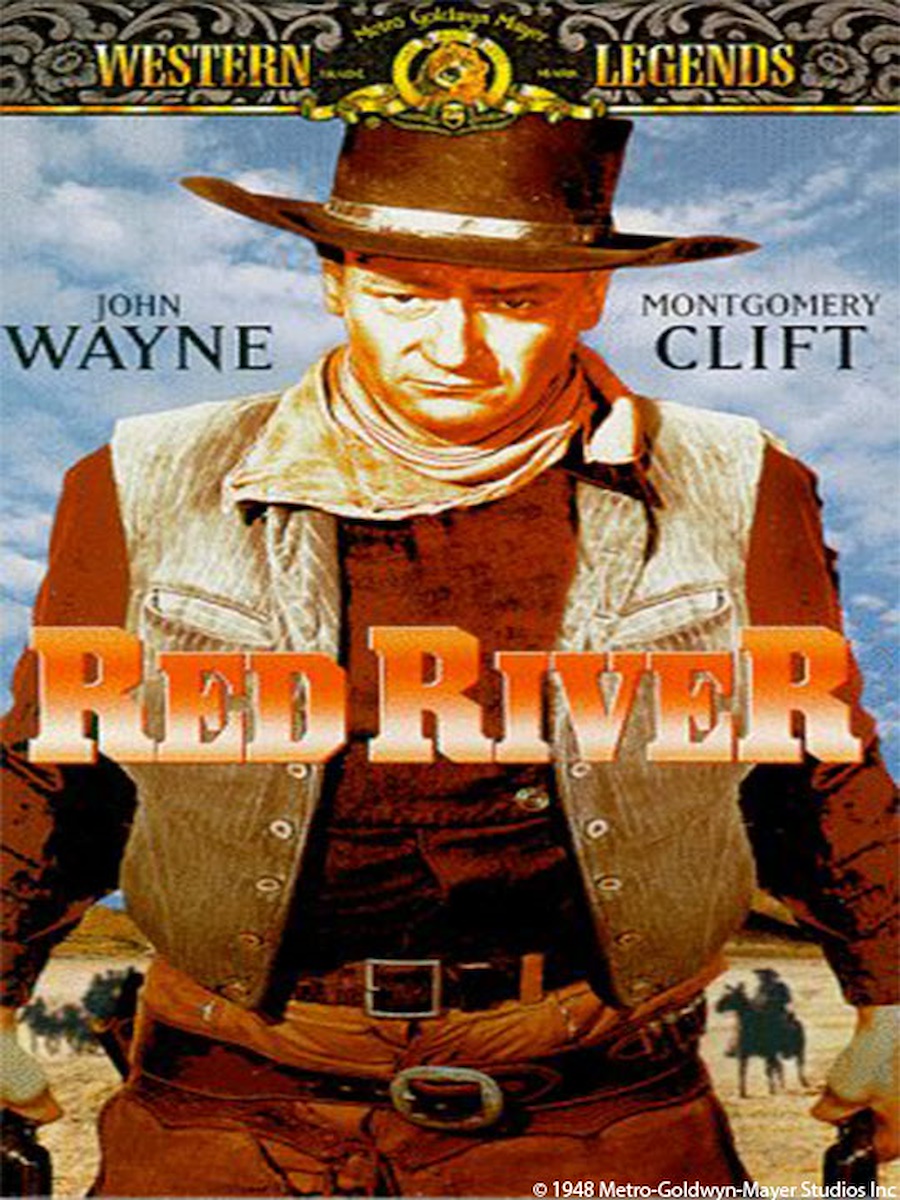

In Howard Hawks, Red River (1948), we see an older, more weathered John Wayne play the villain on screen for the first time. This was certainly a knowingly play on Wayne’s celebrity on Hawks's part. Audiences had become accustomed to seeing Wayne as America’s tough and brave hero, so to turn the tables around on him like that must have been jarring and exciting all at the same time for a genre that's increasingly repetitive. Yet, this too is an example of the western’s "self-consciousness," not unlike Dos Tipos de Cuidado, utilizing celebrity to excite its audience. It shows just how far the image and ideological baggage of both the Charro and the Cowboy had on culture, how conflated an idealized image became with a clear definition of “man”.

image: Red River (1948). Poster courtesy of Swan Films.

If, as Díaz said, la comedia ranchera came to unify Mexican identity through a synthesized and romanticized version of ranchero life, the western’s resurrection came to glorify a mythical history of the American West and thus justify manifest destiny as a necessary part of American identity. If we think about this retelling of history, we can almost always certainly find our hero at the center of it: the all-time perfect American man. One who moves westward, justifying occupation with heroic gusto. Whose virility is unquestioned; it is existential.

Both genres help us look at how our cultural ideas around nationalism, gender identity, class, race, etc., came to be so cemented and widespread through the cinematic boom of the '30s, '40s, and '50s. And though revisiting these romanticized and fictionalized versions of history can be tough at times, these movies can also be insightful, even fun. They’re popular for a reason, and there are many aspects to be enjoyed. Yet, we find it important to look back at them critically and point to the characteristics that are detrimental to our culture at large. To identify and reject those attitudes is what this is all about.

1 ALLÁ EN EL RANCHO GRANDE: LA CONFIGURACIÓN DE UN GÉNERO NACIONAL EN EL CINE MEXICANO.

MARIA DÍAZ LÓPEZ Secuencias No 5 (1996) p9-29

Cinema Azteca: Upcoming Films

December 5

In director Joseph Kane’s Under Western Stars, Roy Rogers plays the role of a rancher who becomes embroiled in a conflict over water rights and land ownership.

December 12

Released in 1934, El compadre Mendoza is a classic Mexican film directed by Fernando de Fuentes (the second film in his Mexican Revolution trilogy).

December 19

The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962)

The classic Western film, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, is celebrated for its complex characters, moral ambiguity, and its exploration of the myths and realities of the American West. Directed by John Ford, the movie stars James Stewart, Lee Marvin, and John Wayne.

January 2

Director Ismael Rodríguez iconic Mexican comedy-drama, Dos Tipos de Cuidado, is renowned for its portrayal of friendship, loyalty, and the contrasting personalities of its two lead characters played by Jorge Negrete and Pedro Infante.

January 9

With its compelling narrative and stunning visuals, Red River has earned its place as a classic in the Western genre, influencing many subsequent films in the genre and leaving an indelible mark on American cinema. Director Howard Hawks’ iconic film stars John Wayne and Montgomery Clift and is celebrated for its sweeping landscapes, memorable characters, and its contribution to the evolution of the Western genre.

January 16

René Cardona version of Cartas Marcadas follows a different storyline than the 1936 adaptation. It centers around the character of Alejandro, a man who falls in love with a beautiful woman named Elena. Their love is threatened by Elena's wealthy and manipulative suitor, Rodrigo.

January 23

A small Mexican village is terrorized by a group of bandits in John Sturges’, The Magnificent Seven. In their desperation, the villagers hire a group of seven gunslingers, each with their unique skills and personalities, to defend their town. The Magnificent Seven is known for its iconic cast, including Yul Brynner, Steve McQueen, and Charles Bronson.

January 30

Me he de comer esa tuna (1944)

Director Miguel Zacarías’ Me he de comer esa tuna is a romantic comedy that follows the story of a young man named Carlos, played by Jorge Negrete, who returns to his hometown and becomes entangled in a series of humorous and romantic misadventures.

February 6

Rio Bravo is celebrated for its memorable characters, sharp dialogue, and director Howard Hawks’ filmmaking style. The film tells the story of Sheriff John T. Chance (John Wayne), who must defend his town against a powerful rancher and a group of outlaws seeking to free their imprisoned comrade. The film includes stars Dean Martin, Ricky Nelson, and Angie Dickinson.

February 13

Based on a popular song, director Juan Bustillo Oro’s comedy No basta ser charro concerns Ramón, a Mexican ranch worker whose life takes a strange turn when his new boss’ daughter, Marta, discovers Ramón’s astonishing resemblance to Jorge Negrete, a popular actor and singer.