Art

January 16, 2019

Viviane Le Courtois on the symbiotic relationship between life and art

We visited Viviane Le Courtois at Processus, the co-working studio space in Denver she founded with Christopher R. Perez. These two are powerhouses. They created Processus (named after the French word referring to a series of processes leading to an unknown result) to facilitate a space for people to share ideas, focus on experimentation, and contribute to the evolution of art and life. The studio has many different kinds of equipment for various mediums, and the space itself is beautifully designed with large warehouse windows, memorabilia, older projects from past series, and pickle jars with different material inside each one.

Le Courtois has a quiet, thoughtful demeanor. She is a jack of all trades; she creates, curates, teaches, and facilitates various communities and discussions for those around her. She is one of the most resourceful people who is not only environmentally conscious, but who also sees the beauty and opportunity in seemingly useless, everyday items and objects regarded as trash.

How did growing up in France influence your art? Whether that be the landscape, home life, your access to materials, the art scene...

I have been making art since I was a kid. I have always collected materials and played with things outside. I grew up on a farm in the middle of nowhere, so I didn’t get to see art until I was in high school, during field trips to art spaces or museums. I dreamt of traveling and being an artist; I looked at maps and at books.

I was very isolated growing up. I didn’t really talk to people, there were no neighbors. I would only see people when I went to school. I used everything when I was a kid. We didn’t have art supplies, so I had to be very resourceful. I would make things out of sticks and mud and pine cones. I used to pick my mother’s flowers and make juice out of them to make paint because I didn’t have paint. And I still use plant juice and dirt to color drawings. I vaguely remember getting in big trouble for picking all of the flowers.

We always cooked, gardened, and foraged berries and nuts. We used to go out to the seaside a lot, too, and I used to make sculptures on the beach and pick stuff there, like seaweed and seashells. I also spent some time with my grandparents in the summer, where I learned crochet and basketmaking. All this was part of life before the internet. We learned to make things to pass time. Later, I realized that my favorite French animated cartoon Les Shadocks inspired my repetitive and sometimes absurd processes.

I studied art at the Ecole des Beaux Arts de Nantes and then in the Ecole Pilote International d’Art et de Recherches, a very experimental art school at the time in Nice. Everything was very conceptual. We didn't learn how to sculpt, we learned how to think and experiment. There was no internet, just books and museums.

That’s where I started to work in the way that I work now. That’s when I made my shoes and started work with food and foraging. That’s when my work started to be about interactions, rather than commodity. The work that I did in my five years of art school in France still inspires the work that I do now. It evolved in many ways, but the root of it happened during those years, from 1987 to 1992.

There is an environmental component to your work. Did you become interested in addressing environmental issues while you were growing up?

Growing up in the country, my family was very aware of environmental issues. We recycled everything and reused everything all of the time. There was no trash pickup so you had to find something to do with your trash. Our trash either went to the compost, or fed the rabbits or the chickens. Or it went in the fire. The glass bottles were refilled. And then the plastic bottles would have to be sent to the village for recycling.

But there was no trash, so I grew up with that idea. Right now even, at my house, I takes a few months to fill the trash can. I compost or recycle or reuse almost everything.

You often use seemingly useless objects, is there something peculiar or fascinating that you find about such objects? Your work often connects to everyday life and common materials that so many of us encounter on a daily basis.

I use everything. My work starts with an idea rather than what I will use. Sometimes I find objects that are interesting and I want to collect them. Or if I find something that everybody might have, like socks or plastic bags, then I put a call out for that kind of material.

A lot of the objects I pick are things that reflect our behavior in modern society, like the single socks, for example. I worked with single socks because I think it reflects a wasteful attitude. We buy new socks instead of wearing mismatched ones if we lose one or make a hole in one. I wear my socks with holes, I really don’t care.

But usually it’s like observing my own life, like finding out that I have all of these mismatched socks, I don't know where they go, and I think that everyone must have the same issue. Or even like finding moldy food in my fridge. I make things out of it. I just made an etching plate with moldy rice.

You seem to use any and every material…

Yes, I prefer to find materials rather than buy them, usually. I use a lot of things from my garden, from my kitchen, or from when I am walking around. I collect things that other people don’t need, insignificant things or forgotten things. I often use social connections to gather materials. I work with a wide range of media, and pick materials depending on my ideas. This requires access to a wide range of equipment and spaces. This is why we started Processus.

You’ve talked about how you find your materials, but what does the process look like once you’ve gathered the materials you will use? Your work is process-based and you mentioned, often repetitive. What is the process for your etchings, like the ones in Octopus Initiative?

I started to grow kombucha in ’94 when not too many people were growing it. You could only get it from someone, you couldn’t buy it online or in the store. I didn’t even know it existed until I had a roommate who was growing it, and then she gave me one and I started to grow it just to drink. But then I didn’t know what to do with the scobies because they keep reproducing and making new ones every few weeks.

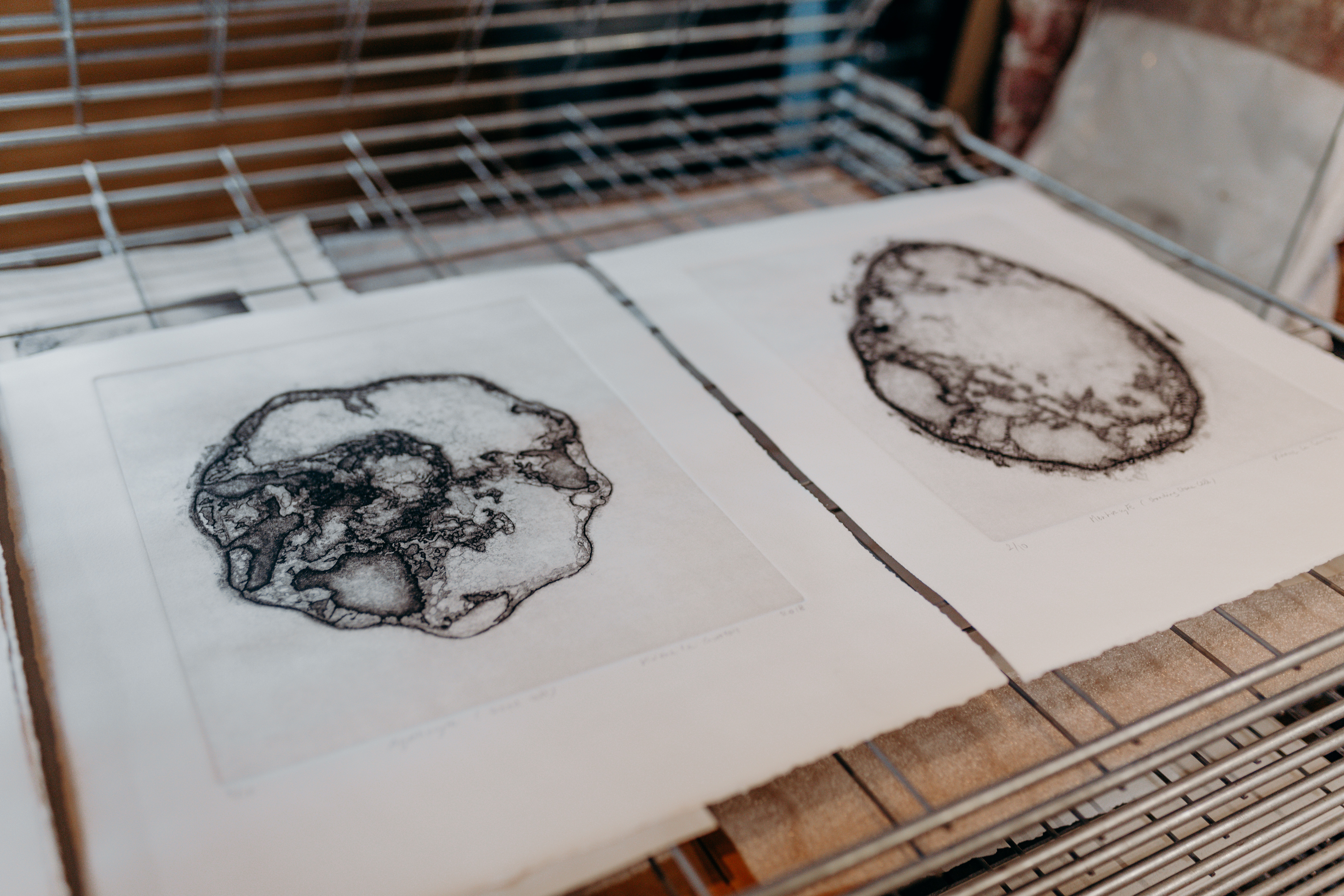

So then, because I can’t throw anything away (laughs) I started to dry them and make things with them. First I was drying them on paper for quite a few years. I had a few shows with dried up kombucha on paper that I would backlight for installations, and then I would also have live kombuchas in some of my installations. And then in 2004, I went back to etching and I thought, what would happen if I tried to put the kombucha on the plate? It depends on the temperature, or if the bacteria is happy or not, I have no control. Sometimes they are not as strong as other times.

It takes a very long time. When artists make etchings traditionally with nitric acid, it takes 15-30 minutes. My plates take months. It took me the entire six months to make the plates for the Octopus Initiative. Most of them were ready to print only two weeks before the project was due! I had to print for 14 days straight. I took a two-week vacation just to print the whole series!

One part of my work is really about chance and not knowing what happens until it gets there. I have to rely on natural things, so I have no control. It’s all about process. I like the finished work but the time that it takes to get to something is really important to me. I always pick processes that take forever, I don’t know why. I think it’s just part of my personality, I have to see things get somewhere. I would not like to start something and finish that same day.

So there is a really big emphasis on process, and the actual time it takes in all of your work…

Yes, and on life too. Art and life for me are not separated, they are the same thing. We don’t know what will happen next. Things happen and shape who we are and where we go in life. Every time we cook the same thing it may be different, every time we take a walk we may encounter something new. It has always been about process, and time, about linking art and life on a daily basis.

I started to make shoe sculptures in 1991 as a way to transform material with the act of walking. Over the last 27 years, people have looked at me with disgust or with admiration. They have become conversation starters everywhere I go.

You described the process, but what was the idea or concept behind the kombucha etchings? If there was an identifiable one you can verbalize.

The idea was to create different organic shapes. Most of the prints I made before with kombucha were round or oval. For this series, I made a lot of ceramic containers to make the kombucha grow in different shapes, to actually better control their shapes. They are inspired by different shapes of cells and microscopic forms. Different things happened by chance in the process and then I made up names with Greek, Latin, or Breton roots, according to what they looked like.

I would like to see what the winners of the lottery think about it, after looking at it for 10 months. Does it change their life or make them think differently? I always analyze people’s reactions to my work.

You define art as being able to remember what you see. Is that as broad of a definition as you would give to art?

I think so. I think if someone remembers a place, a work of art, a smell, or a taste, that means they connected to it in a certain way. There are different ways one can connect, whether it is visually, conceptually, or emotionally. I know if I walk by things and don’t care about it, I won’t remember them. Ninety percent of the work I see is work I don’t remember; probably more than that. It’s rare that I see something that sticks in my mind and I look at a lot of art—but I am really picky.

You have been teaching and instructing for a while now. With all of the experience you have, is there any advice that you have for young artists?

I enjoy teaching high school and college students the most. That is the time they are really developing their ideas and personalities as humans and as artists. My advice would be to not give up, to not follow trends, to do what you like even if it may be out of the norm. Being an artist is not easy, and it is hard to stay true to what took you there at first. It is hard to make a living doing experimental and conceptual work. You have to make sacrifices and compromises, you have to work a lot and live with less, and keep doing it until someday, something might happen. You have to be selective and only show where you want to show. But money should never be the goal. You have to follow deadlines, be able to write and talk about your work…do not limit yourself because you do not have the equipment to make what you want, find a way to do it. But most of the time, things happen through social connections or from one show to the next and sometimes there is not enough time to think of what is next.