March 1, 2021

March is Women’s History Month!

Throughout the month of March we celebrate Women’s History Month! It is a dedicated time in the year to recognize the monumental impact women have made to the United States in history and contemporary society.

The first observance of Women’s Day started in 1909 in New York. In 1911 the first International Woman’s Day was held and continues to be observed March 8. In 1975, the United Nations commemorated the date and International Women’s Day was formally recognized globally. As for Women’s History Month in the United States, it began as a week-long observance in the 1980’s thanks to a group of women in Sonoma County on an educational task force organized a week in the schools to celebrate the achievements and contributions of women. It was not until an act of Congress in 1987 that March was formalized as Women’s History Month.

In celebration of Women’s History Month, we asked our staff to share artists/creators who have impacted their lives or inspired them in some way.

Augusta Savage

“I was a leap year baby, and it seems I’ve been leaping ever since,” Augusta Savage once said in reference to her life and career.

Augusta Christine Fells was born on February 29, 1892 in Green Cove Springs, Florida. She was the seventh of fourteen children to Cornelia and Edward Fells, a Methodist minister. Augusta’s artistic development was not encouraged by her father and she is quoted saying, “My father licked me four or five times a week, and almost whipped all the art out of me.”

Augusta married in 1907 to John T. Moore, her only child born the following year. John died shortly after the birth of their daughter, Irene Connie Moore. She remarried in 1915 to James Savage, keeping the name throughout her life after their divorce in the 1920's. In 1921, Augusta moved to New York City. Unable to afford the tuition at the School of American Sculpture, she applied to Cooper Union, a scholarship-based school in NYC. She beat out over 100 men on the waiting list and received full academic and living support. She completed the four-year degree course in three years.

In the peak of the Harlem Renaissance in the mid-1920’s, Savage began to earn a reputation as a portrait sculptor and was commissioned by prominent figures such as W.E.B Du Bois and Marcus Garvey. In 1923/24, Augusta was awarded a scholarship to study at the Fontainebleau School of Fine Arts in France, but the scholarship was denied once the committee learned she was Black. Augusta fought this decision and used the press she garnered as a tool to bring attention to the matter. The committee did not budge on their decision, however.

She continued sculpting, during this time, creating her best known sculpture, Gamin. The bust portrait is modeled after and shows with great detail the physiognomy of her nephew, a skill that she was exceptionally brilliant at. The bust is made out of white plaster, and because Savage could not afford to cast her busts in bronze, she used brown paint and shoe polish. Shortly after creating Gamin, Savage was awarded a Julius Rosenwald Fellowship to study in Paris in 1929.

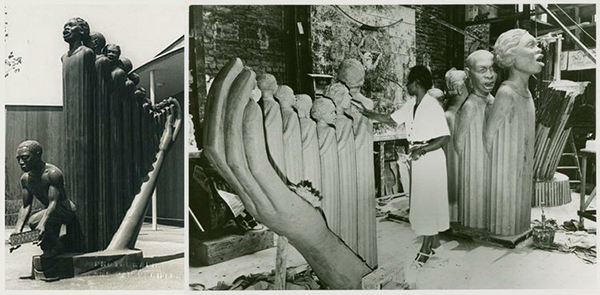

She returned to New York in 1932 and established the Savage Studio of Arts and Crafts in Harlem and became an influential arts teacher within the community. Savage became the first African-American artist to join the National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors. For the 1939 New York World’s Fairs, she was commissioned to create a sculpture symbolizing the musical contribution of African Americans. Inspired by the lyrics of NAACP leader James Weldon Johnson’s anthem Lift Every Voice and Sing, Savage sculpted a sixteen-foot sculpture that was to be named after its inspiration. However, the World’s Fair officials changed the name to The Harp.

The sixteen-foot sculpture depicts twelve Black children singing in a choir. The strings of the harp are formed by the folds of the choir robes and the soundboard of the harp is shaped to be the hand of God. Unfortunately, The Harp was destroyed after the fair, as was much of Savage’s work.

Augusta Savage had an awareness that her life and her work would live on in others, inspiring the careers of a flourishing generation of artists like painter Gwendolyn Knight and painter/sculptor, Charles Alston. It was important work of hers to create spaces for Black youth to explore their creativity and networks for Black artists, “I have created nothing really beautiful, really lasting, but if I can inspire one of these youngsters to develop the talent I know they possess, then my monument will be in their work.”