Art

October 10, 2018

Laura Shill on Art and Giving Yourself Permission to be Embarrassed

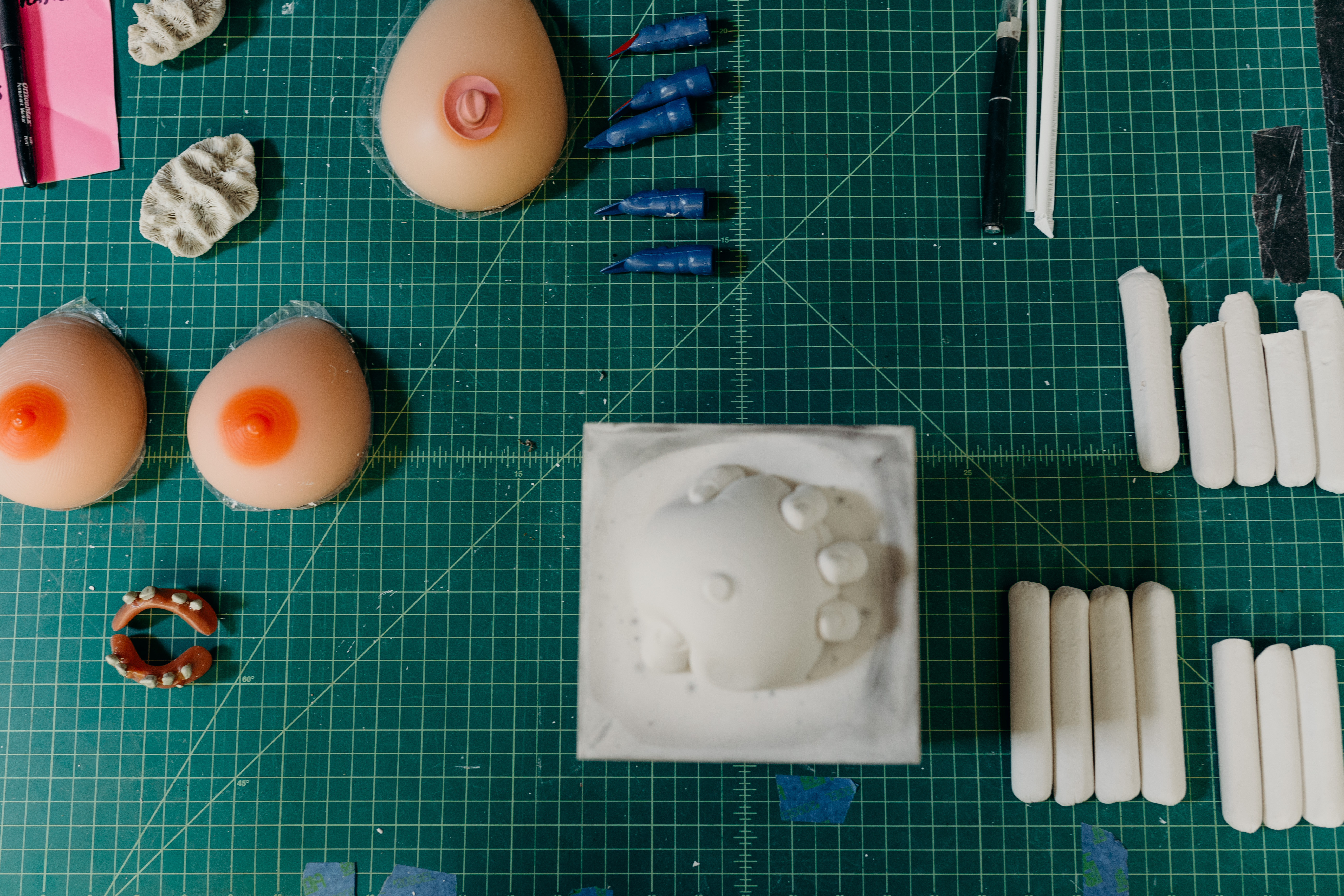

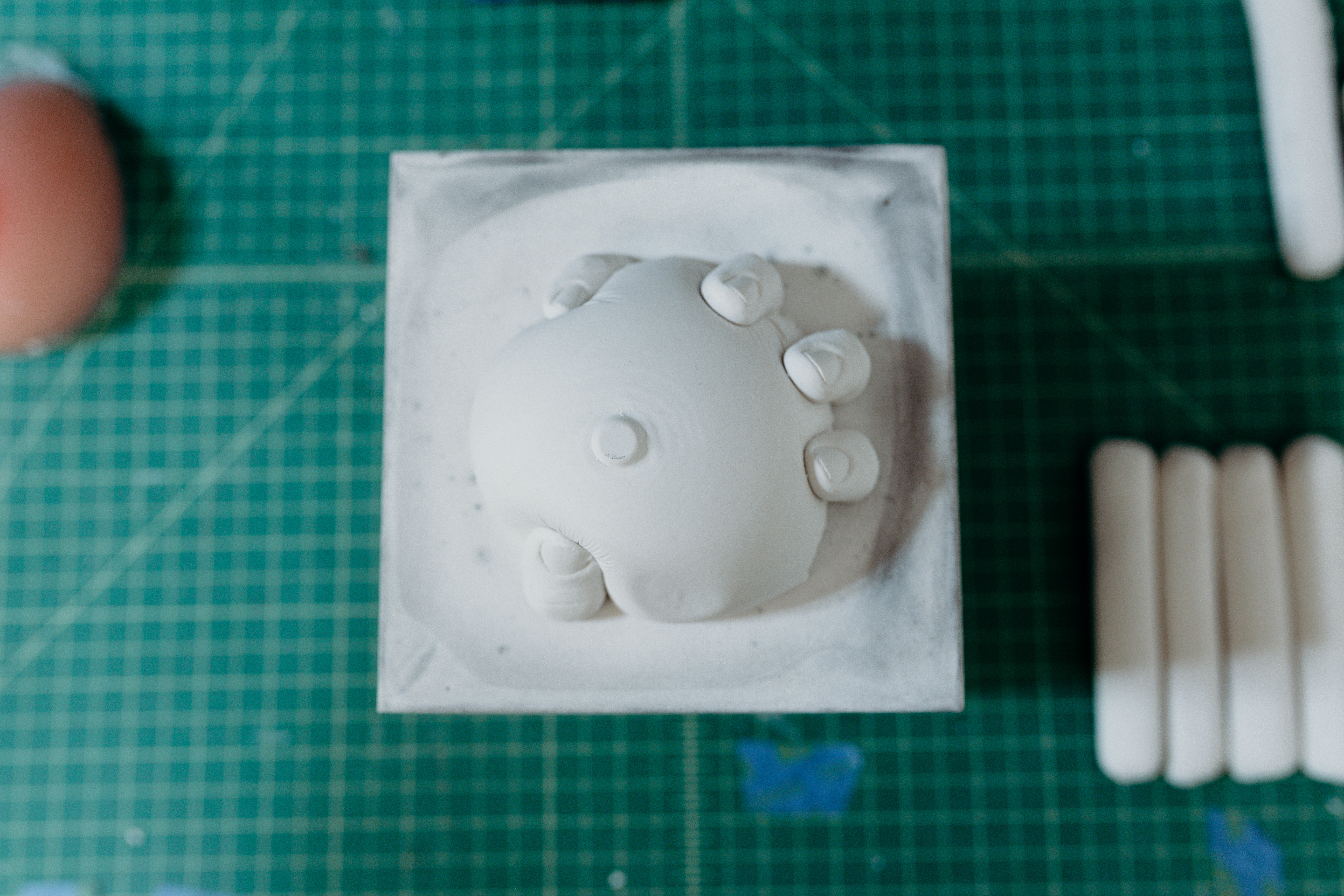

Laura Shill welcomed us to her studio, in a building that is home to many Denver artists. Upon our arrival she gave us a tour of the building and a peek into other artists’ creative spaces, each one looking completely different from the last. We then circled back to her studio, a space that is adorned with electric silver spandex and various sculptures of boobs, hands, and hands grasping onto boobs.

Shill is deeply kind, authentic, and brilliant without being pretentious. In our conversation she thoughtfully reflected on unfulfilled desire and loneliness in an age that is bombarded with media and perhaps a pseudo-interconnectedness.

How did you know you were an artist?

You know, it took me a while to admit it, because it seemed like a frivolous idea with my background and upbringing. I kind of came to it by becoming a photographer first. I grew up in Alabama to working-class parents, and so, saying I wanted to be an artist would be like saying I wanted to go into some absurd profession that I had never seen modeled in my lifetime. So, I studied journalism because I have always been interested in writing and telling people’s stories and wanting a reason to have access to other experiences outside of what I knew. Then I started using the camera to tell those stories as a photojournalist. That was sort of my gateway, through photography.

I felt like I had to prove I could make a living doing something creative before I could admit to myself that I wanted to be a professional artist. I had a photography career that was paying the bills and then I had this parallel art practice that I was sustaining on the side, and I kept those two things pretty separate. Then I just decided at a certain point that I wanted to go for it. So, I applied to MFA programs all over the country in places I wanted to live and outside of the Deep South. I ended up at CU Boulder right after they built their new Visual Arts Complex and felt like I was going to be showing up at the start of something. And then, Denver just embraced me and has given me a lot of opportunities that have encouraged me to keep doing what I’m doing.

When did you start addressing the ideas that you do in your work? Like viewer and subject, disclosure and concealment…

My first photo class as an undergraduate at the University of Alabama was where those ideas started to emerge and I began digging into my embarrassing ideas. This is something I try to instill in my students when I teach—to embrace your embarrassing or dumb ideas. Do them—they might turn into something important. And even if they don’t, they’ll make you get comfortable with your own voice.

(Laughs) I had a pretty embarrassing Southern Gothic aesthetic. We would go to an abandoned asylum to make our edgy photos. But, even in grad school I would ride my bike to get around and I would be taking soft sculptures to class and it would be like a vagina dentata strapped to my back and there I am, just on my bike riding through town. Anytime I transport my work I’m always like, this may be more interesting than the sculpture itself, just the performance of me carrying it from point A to point B and struggling with it. It’s embarrassing but also kind of gleeful.

I think now, I’m less embarrassed by my ideas and less afraid to spend time exploring something that might be stupid and just trust myself more and trust that I can get a thing done even if I don’t know what the thing is.

You need to have a videographer with you because that sounds hilarious and awesome. Where did the idea of the “pink tubes” sculpture at MCA Denver in 2016 come from?

People always ask me that and I kind of don’t know where it came from. It was probably just a dumb joke. That’s how the Absent Lovers started…a lot of it is me making a dumb joke to myself and then being like, well, let’s see if I spend five years on the thing if this dumb joke can turn into something. But that (the pink tubes) just got made by a thousand invisible hands performing unpaid labor on my behalf. And that was another way Denver facilitated something I couldn’t have done on my own.

Did you create Absent Lovers for Octopus Initiative specifically?

That was an existing body of work that is still ongoing. Absent Lovers first started when I was in this group called the Denver Collage Club. I was invited to be part of a print exhibition on Valentine’s Day and the theme was romance and I was like alright, how can I subvert that? And so I was at the thrift store, where I am often looking for materials, and I was looking through the romance novels and looking through my collection of cute animal images and I started cutting out the men and having them embrace giant cats or a giant chihuahua. So that’s how it started, was with a dumb joke—making images of men passionately embracing a chihuahua or a cat. But then the erasures themselves ended up being more profound than the joke was. And then it just unfolded and revealed to me power dynamics: the man always above the woman and the impassioned embrace, that is sometimes violent or longing. There’s just a lot to mine…there’s a lot of meat to chew on.

I’m up to about 100. I always imagined that I would create 100 Absent Lovers and then I would stop and make a book and circle it back to its original form. But now that I’ve hit 100 I’m still not ready to stop because, I mean, there are just so many of these books and they’re still being churned out and they’re still for sale at grocery stores and everywhere else. It’s still a rich source of inspiration for me and I’m just going to keep going with it until I get tired of it.

The novels, to me, are ultimately an expression of unfulfilled desire and loneliness and fantasy. They are so ubiquitous. I always read the first page and the last page and the synopsis. The plot lines are almost identical for each one. The man pursues the woman, she refuses his advances for as long as she can, thus ensuring her chastity, until she finally relents, they get married and live happily ever after.

It’s so formulaic. On one hand, it’s intended to address female desire but on the other hand it reiterates stereotypes about being a woman just seeking security and not being as interested in pleasure as men. It’s endlessly fascinating.

It is. What does the actual process of making Absent Lovers look like?

I photograph them, and then I digitally remove all but one lover who gets trapped in that void of white and expression of impassioned anguish. Then I’ll make a negative that is to scale digitally and then I’ll bring that into the dark room.

When you’re finished, do you reimagine the figures in a new scene or is isolating them in the void where it ends for you?

Yeah, pretty much, the isolation distills it down to its essence for me, that it’s ultimately about absence. And then the titles are the titles from the novels themselves. Some of them are really funny. Even if the images aren’t ideal for the process, if the title is too good I just have to make it work.

Have you heard from anyone who has won one of your works in the Octopus Initiative lottery?

Yeah, a couple of people. Some people are like, “Oh your art is over my toilet!” (laughs)

Yes! That’s amazing. So how do your ideas translate from medium to medium?

The idea determines what the form will be. My ideas are informed by everything around me, whether it’s a material, paying attention to the news, thinking about how our species is changing, or thinking about my own relationship to technology and trying to be critical of the way I spend time on Instagram or consume media. I ask myself if it is making me lonely, is it making me feel frenzied…I just really try to pay attention to what’s going on in my life.

A lot of times it circles back to absence, and brings me back to the photograph and the representation of the absence of the thing that’s being pictured. It seems to be a thread that returns through most of my projects.

You mentioned technology. Has that caused a shift in your work and your life?

My relationship to my cellphone is something I think about a lot. And my relationship to other people and whether those are authentic or not and how you can know. Even the way we communicate with each other is increasingly confusing for me. I probably know what 50 percent of text messages actually mean. There’s so much speculation now that you have to do on each side of a conversation because the way that we are communicating. Often you’re just kind of lonely and confused on your side, and maybe the other person is as well. That’s a thing I’m thinking about a lot…that this is how our species is evolving and changing very rapidly in ways that I think can improve our lives and make things more convenient but that are also making us very lonely. I have an intimate relationship with this device and it knows more about me than I know about myself.

Intimacy is fundamental to what is it be human, and it’s becoming so confusing to people and harder to navigate than it really should be.

Thanks for sharing all of that.

Yeah, you’re welcome!