Art

June 26, 2019

Joel Swanson and the art in language

We got a brief crash course on linguistics through the lens of art and technology from Joel Swanson, one of our recent Octopus Initiative artists.

Swanson’s studio is a monochromatic neon dream. He has a hodgepodge of words plastered to the wall above his desk. The composition notebook patterns and pink pearl erasers scattered about reminded us of grade school.

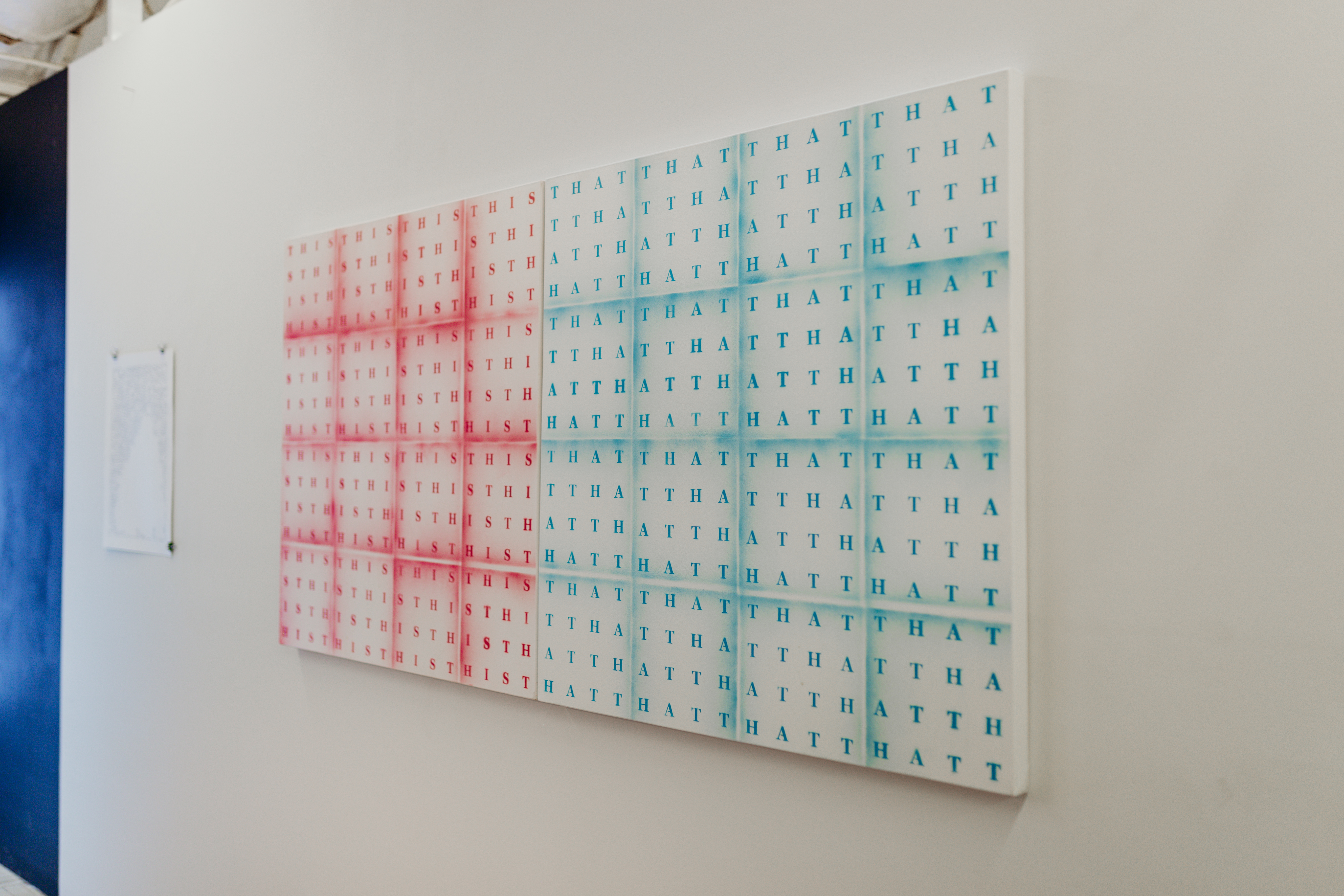

Swanson examines what is so ingrained in our world, our relationships, and our communication that it often goes unnoticed or fails to be critically examined: he employs commonly used words and phrases and isolates them, challenging the viewer to pause and think differently about the way words shape our lives—and the way we shape words.

Swanson is charming, humble, and quick on his feet. He wears many hats as an artist and a professor, and his spirited and thought-provoking responses to questions surrounding art and the relationship between language and technology were endlessly fascinating.

Your work is pretty different from the other Octopus Initiative artists, meaning that it is heavily text based. How did you start working with language and technology? Why the interest in working with words?

I can trace my interest in language back to elementary school. I remember loving (and at times hating) English and grammar classes. There was a sense of control that came with being able to dissect language and study its underlying rules and structures. I would diagram sentences just for fun.

I’ve also always been an avid reader. When I went to college I struggled with choosing between English or art as a major. My father was very happy that was I torn between two lucrative fields. I ended up studying digital art with Mark Amerika and became interested in experimental digital narrative and hypertext, these places where literature and digital technology converged. I went to graduate school at the University of California in San Diego to study computing and the arts. To be honest, grad school was like an art boot camp for me. I was completely unprepared. I went through some really nasty critiques that shook my confidence, but it helped me realize that I was really interested in language itself. This experience turned me on to linguistics and language-based, conceptual art practices.

I think in another life I would be a computational linguist. Perhaps in some ways I am, I just create art instead of formal research. I’d rather make art than write papers. Art allows me to explore questions and ideas that are often missed by the “rigorous” research.

How do you decide if a word or a phrase is worth examining and exploring further? What does that process look like—of selecting a word or phrase—and how does it evolve into a completed work?

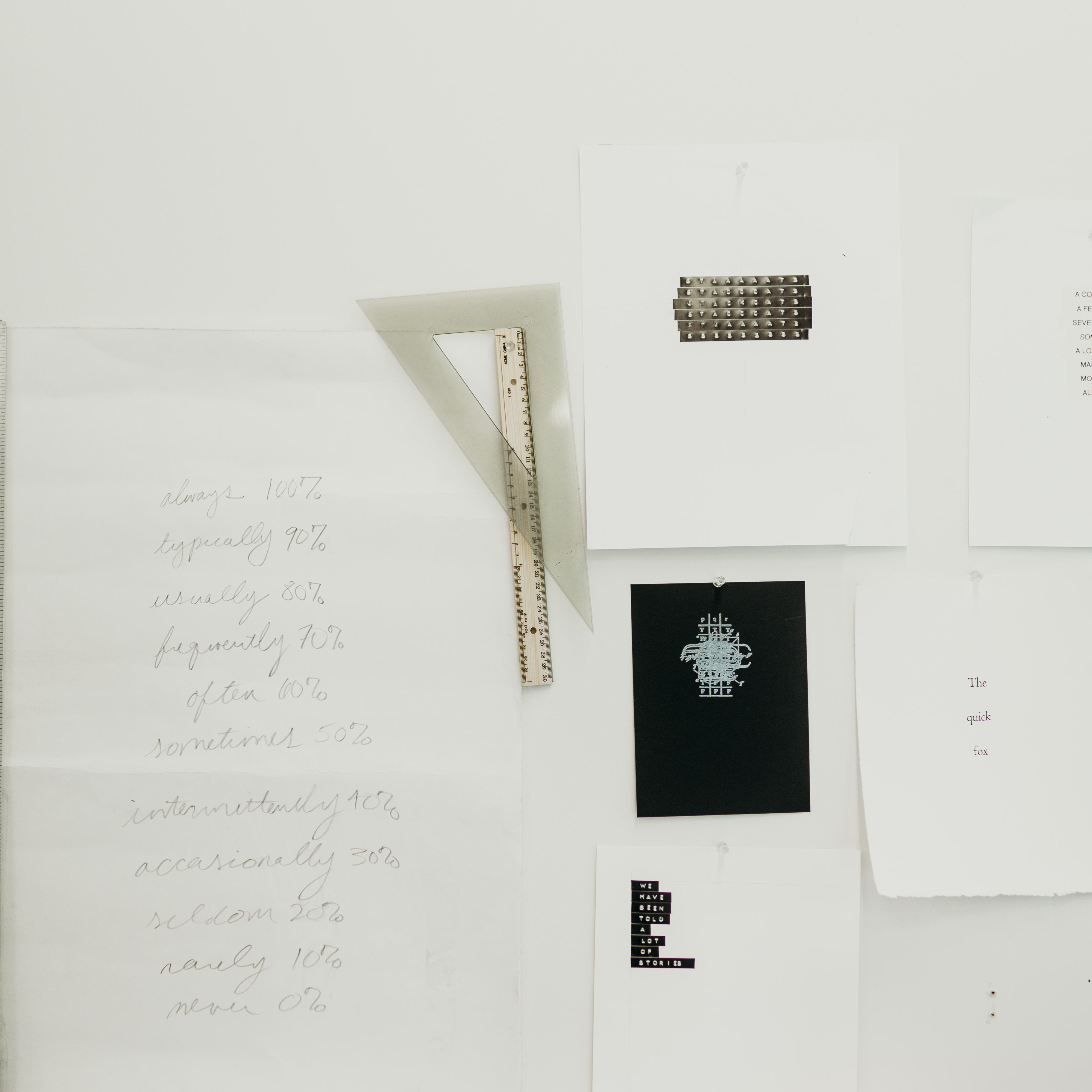

Typically I’ll be reading a newspaper or I’ll be driving and see a road sign and a word or phrase will just seem off—it will spark my curiosity. I’ll write the word or phrase down in my sketchbook and just start playing with it. Sometimes there will be enough there to make a work, but usually I will have to let it marinate. I have a long list of these ideas in my notebook and anytime I’m feeling stuck, I will read through that list and see what grabs me. Things need time to bake in my brain. Sometimes an idea for a work comes immediately, sometimes it will take years for an idea to resolve itself.

I have to say that my process is very different from other artists who seem to develop work very linearly. I feel very haphazard. I love being in my studio but ideas don’t typically come to me there. I can’t force myself to be creative, I just need to put myself in environments where ideas come to me. Ideas come to me while running, reading cheap sci-fi, or playing video games. It’s like I have to turn my brain off a bit to let it do its thing. As artists, it is really important to know what kind of spaces and environments feed us creatively.

A lot of your work uses language that many of us know and use. Are you interested in the accessibility of your work?

I certainly want my work to be meaningful to everyone, but one of the pitfalls of working with words is you have to pick a language, and that language will dictate your audience. English is my first language, so it makes sense that I would work with it. But I’m very sensitive to how English has been used as a colonizing technology.

For example, most computer languages are based in English, so if I build a program or website that has its content in another language, it still needs to be programmed and structured in English to be “universally” accessible. It’s subtle, but this is one of the many ways that language exercises power.

I’ve exhibited a few times internationally, and I was very sensitive to how my work was read (figuratively and literally) in those contexts. I never want to communicate that I view English as a “default.” Language is a technology, and I hope that people see my interest in critiquing that technology first and foremost.

Recently I have been exploring doing work in other languages. I have been developing a series of works based on the translation of French idiomatic phrases. There’s a rich history of conceptual art in French, so it is an exciting new space for me to explore.

Do you work with the words physically, or is it computer based? Is there a difference for you in working with palpable materials versus digital?

I’d say it's around 70% computer, 30% analogue. Programming is a great tool for exploring certain ideas, but I still need to sketch and doodle with a pencil and paper. I view the digital and the analogue as symbiotic. Different ideas need to be explored through different mediums and technologies, and I am thankful for my background in computing as it offers me useful, practical, and conceptual perspectives.

Do you handwrite the fonts and typefaces that you use?

Not really. I have made typefaces but I would call them conceptual experiments that use a font as a delivery mechanism. I don’t have the skill or patience to create a useable typeface, but I have the utmost respect for typographers who do.

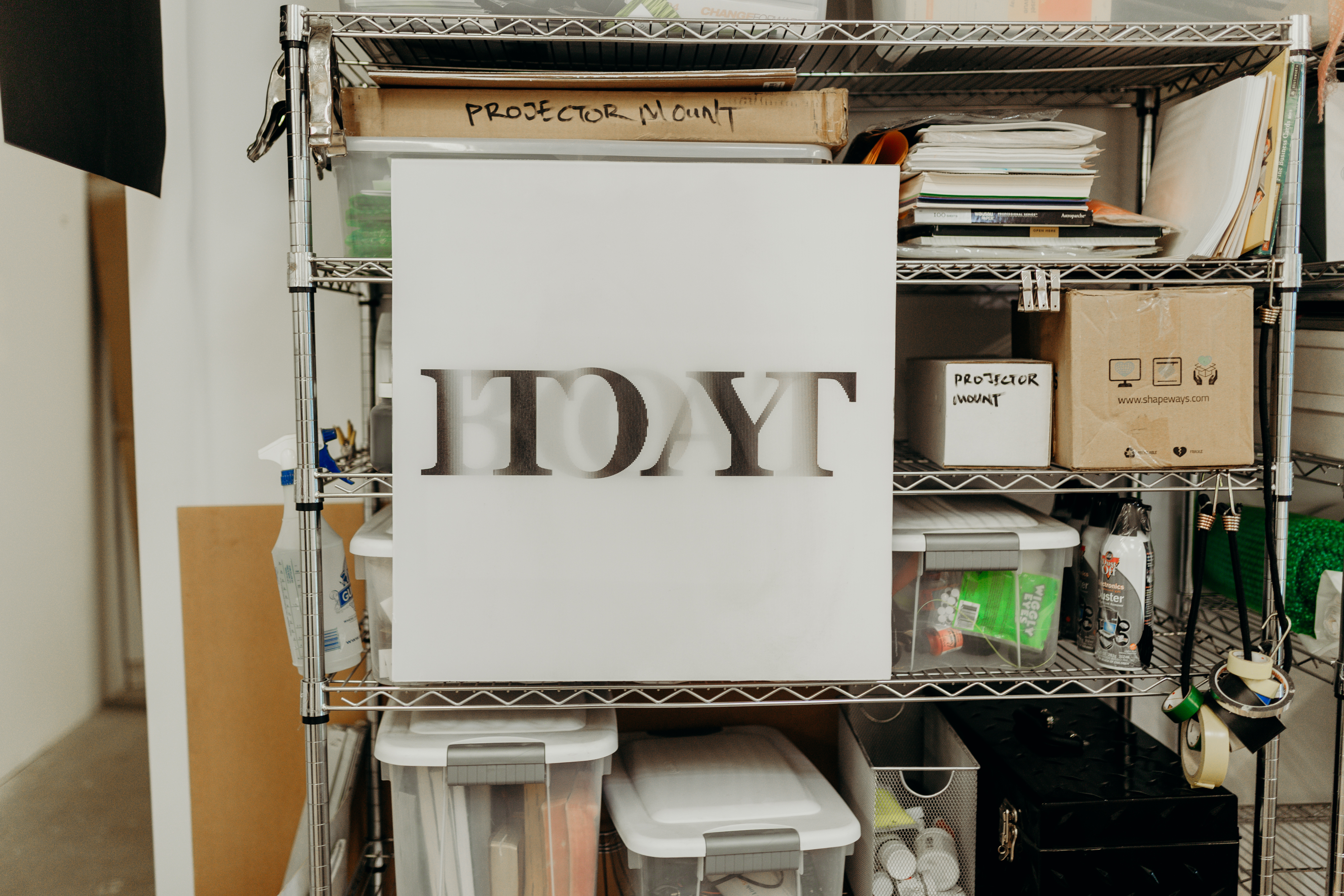

In graduate school I noticed that all my art heroes consistently worked in one typeface. Barbara Kruger used Futura Oblique, Lawrence Weiner uses a custom version of Franklin Gothic (that he designed himself), On Kawara uses a quirky adaptation of Gill Sans, even Jenny Holzer has her quintessential LED type. This inspired me to pick a font, and I chose Georgia.

I picked Georgia because it’s not a very polished or sexy typeface, at least by today’s standards. It was made for low resolution monitors in 1993 by Matthew Carter as a digital stand-in for Times New Roman. Because of the technical limitation of low resolution monitors it has this kind of odd but distinctive quality—it’s anachronistic. There are many similar more “beautiful” typefaces, but I like the history and quirkiness of Georgia. It might seem cheap or out of place, but that is what makes it distinctive.

So you’ve committed yourself to that font. Do you ever want to step outside of it?

I love parameters, so I enjoy restricting myself to one typeface. I need a good boundary to work with or against. I find it easier to be creative with parameters as they help me focus on the concept behind the work. Only using one font helps me avoid getting hung up on “picking the right font,” which feels more like a design question than an artistic one. Having no parameters can be groundless. The most difficult assignment I can ever give my students is to do what they want.

Yeah, absolutely. What’s been one of your favorite things about teaching students and young artists?

I am currently teaching an introduction to visual programming course at the University of Colorado Boulder. It is an interdisciplinary course, so many students come into the class feeling apprehensive about programming. Teaching students that you can use programming as a tool for creative expression is really exciting. As a teacher, it is rewarding to take students from a place of anxiety about programming to a place of confidence and mastery.

We are told so many narratives growing up, like “math is hard” or “programming is hard.” We internalize these narratives and they end up negatively influencing our choices. One of the most important things I do as a teacher is to help my students rewrite these narratives.

Whether it’s advertising, the media in general, or social media, language is absolutely everywhere. Do you ever feel bombarded, or do you see it as unlimited?

Language is everywhere, but I hope my work creates a space for people to contemplate words and their power.

I recently installed a public sculpture in an alleyway in downtown Denver that spells “YOURS” and “OURS” in white neon; the “Y” blinks on and off to alternate between the two words. An alley is a thoroughfare between buildings and streets, but it’s also a marginalized space. Who really “owns” an alley? As social spaces, alleys can be seen as metaphors for our society.

We use the words “YOURS” and “OURS” everyday, but they are really powerful. They influence our notions of ownership, nationality, and identity. I want my work to give people the chance to really think about these words and how they relate to their lives. So, to get rid of everything else, get rid of the bombardment of advertising and social media and let’s just think about how we use and abuse words.

Ideas of space and place come up in your work. Both the ways the text takes up space formally, and the physical places your work is installed. Do you recognize or explicitly integrate these ideas in your practice?

I think that comes from my interest in indexical language or words that only mean something within a specific context. When I say, “I am sitting here,” “I” refers to myself. If you don’t have context or reference to attach it to, the word becomes ambiguous. I am fascinated by this subset of words that are meaningless without a context. So in my work I frequently use words such as “here,” “there,” “yours,” “ours,” “this,” and “that.” Context is about space and place, so the relationship between words and location is a significant aspect of my work.

What was creating this new body of work for the Octopus Initiative like for you? It seems different from previous work.

Making two dimensional work on a smaller scale was really fun for me. As I said earlier, I enjoy working with parameters, so coming up with a body work for the Octopus Initiative was an exciting challenge. I was able to include some older works with some newer works, so I feel like the collection is a great sampling of my practice.

Three of the newer works I included are based off of those composition notebooks that we used in high school—the ones with the distinctive marbled black and white pattern on the cover. These patterns are interesting because they relate to language but aren’t linguistic. I started tracing these patterns and filling them in with a Sharpie. I remember a history class in high school that was particularly boring. I would sit there and fill my notebook with these highly detailed squiggly patterns. I find this mindless drawing practice—which comes from a place of boredom and tedium—to be really interesting. It’s not drawing in a “high art” sense, but it is a very familiar act that we can all relate to. It comes from this very unique mental and physical state of being—like a meditative mark making. Anyway, these ideas are developing into a new body of work that I am looking forward to exhibiting this winter.

Why do you think language has such power in art?

Language is ubiquitous, almost automatic. Whether it’s English or some other language, we all use some system to communicate, and at some point, that system becomes second nature.

We read, we listen, we speak, we write, but we don’t think about it; we’re not critical of these practices. That’s the subtle power of it—language shapes us as we shape it. It affects how we think about things, it shapes how we perceive the world.

My goal with my work is to take that subtle but very potent power and make it more visible. Through repetition, or playing with the dimensionality or context of language, I hope to make language more difficult—or at least different—so that we can see language from a new perspective. I hope my work makes people more critical of the role that language plays in our lives.