Art

March 26, 2020

George P. Perez and his relationship to the photograph

We met one of our Octopus Initiative artists, George P. Perez, outside his studio at The Temple, an artist haven in RiNo. Perez greeted and treated us like we were old friends, offering us coffee from his poppy red french press and welcoming us into his sun-drenched studio space as if we’d been there countless times before.

Perez’s primary source material is the printed photograph, and we were eager to dive into conversation as to what it’s like working with the ubiquitous material. He expanded upon his relationship to photos of people and scenes he’s never encountered before, discussed his extensive photo collection, and provided insight into what it’s like being a part of the Denver art scene and the Octopus Initiative.

In our conversation, Perez described his process as intuitive and his manipulation of the photograph as investigative and playful. Perez’s work is often nostalgic, and allows the viewer to place themselves in the scene even though the characters are partially torn off, altered, and strangers to the viewer.

Why the photograph? How did you get started and how did it become your main medium?

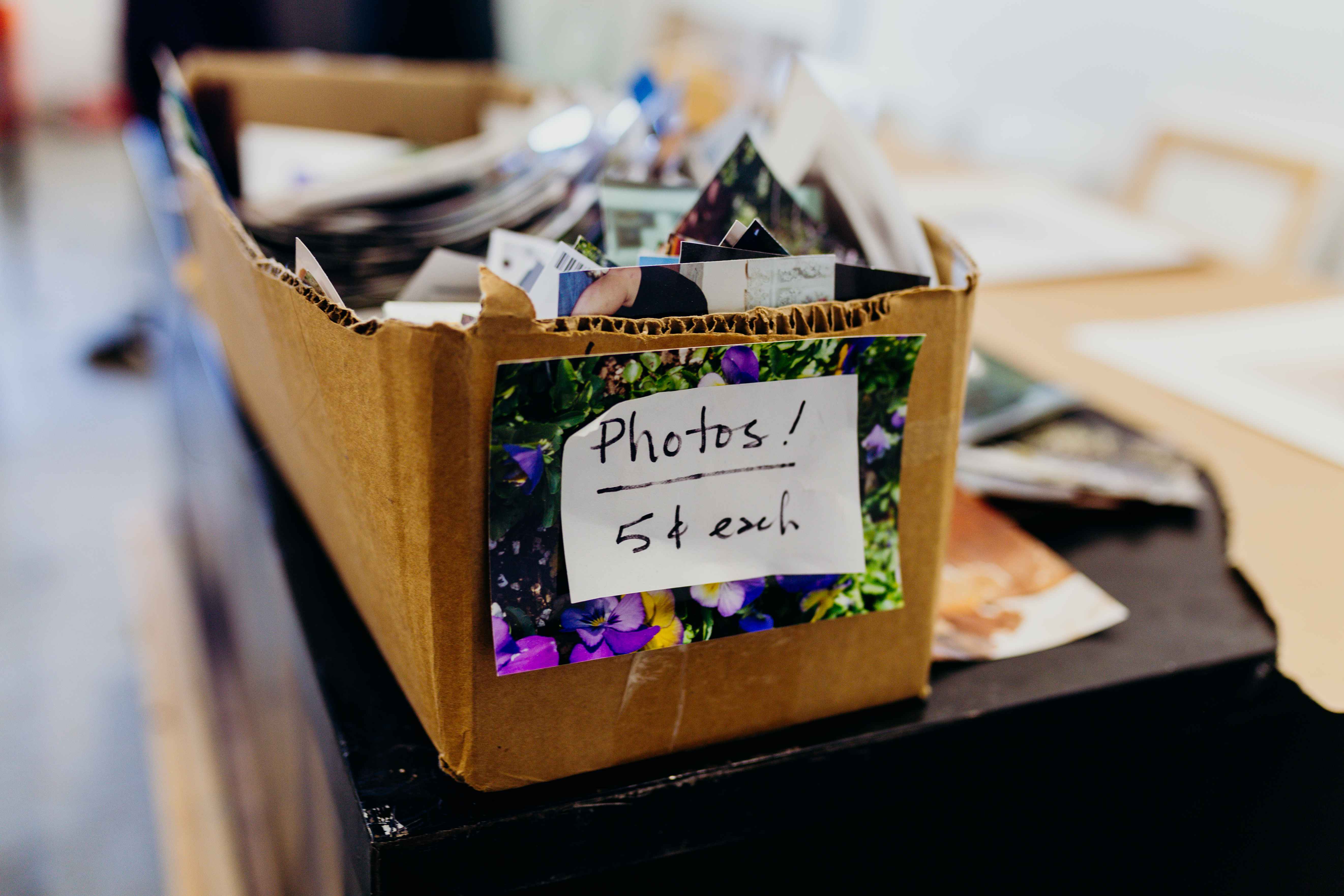

I work with found photos. Well, I don’t like to call them that. I call them claim photographs since I’m the one going into these places—like thrift stores or antique shops—to purchase them and use them as my own, though sometimes they’re generously given to me. Oftentimes these photographs have been forgotten or let go of. I want to use or recycle what images already exist around me.

I’m starting to realize this might have all started from looking at my personal archive—my personal family albums or pictured genealogy—and not seeing an extensive amount of photographs. I think I started collecting photographs to fill a void.

I would have this feeling of amazement, but also sadness, that no one wanted or cared to hold onto these photographs anymore. I thought these small objects needed a home and now I have accumulated thousands upon thousands of photographs to use as my material.

I am very much interested in the everyday and the mundane, and a lot of these photographs tap into that. These extensively documented scenes such as people’s homes and other places don’t really mean too much to me personally and can be boring, but that’s also what’s really interesting. There’s something so direct about a subjective feeling of why the image was captured that I will never know personally, and I’m gravitated towards those types of images.

Your work often addresses the personal and the collective experience. Do you prefer to stay away from your personal archive, or do you use family or personal photographs in your work?

I used a personal photograph once. I tore the only black and white photograph of my great grandfather on my dad’s side, just to see what it felt like tearing it up. I did it without permission from my folks and had the work up for an exhibition, which of course, was where they found out. It was my youngest sister who recognized the altered image, not my dad. She laughed at me like I’d been caught in my prank. My dad didn’t show much remorse, but I could tell he was saddened and confused about it.

From that moment it clicked that there is a power of vulnerability in certain images. Since then, I haven’t used personal images as my source material. They are too intimate, too private, and too closely related to me. I am more interested in using the abstract plethora of everyday people—the stuff that’s already out there. I don’t necessarily want to talk about myself.

Your work has such an appeal perhaps because it depicts universal scenes that are present in our culture. Would you say removing yourself helps you create a scene the viewer can truly insert themselves into?

I think so. The practice of photography is very much a part of our culture and we continually capture these universal scenes in different ways from generation to generation. It’s like celebrating a birthday, or the routine of watching TV during dinnertime, or even holding the door for someone. Many people have done this same thing and recorded it on camera, and chances are, you have also taken a similar photograph. We practice this aspect of photography on a day-to-day basis, sometimes not even really knowing it. It’s definitely a part of our culture: these beautiful celebrations, habits, and gestures.

I’m already so far removed from the start before the image has been altered, so I try to push that feeling of separation even more with the viewers. There’s a familiar thing about the image, but you don’t have all the information to understand it entirely, and that's where you're able to insert yourself. You fill in the blanks with what you remember or know.

If a photograph can evoke nostalgia, with not so much detail, that’s the kind of image I am using.

Walk us through your process. How do you determine if a photograph is worth examining or using?

I think it comes down to an image that is so separated or distant that I don’t really know what I’m looking at.

For example, my portraits. They’re so intimate already. You look at the eyes, the nose, the mouth. They’re a person and they have character. When I reach the end of my process you’re not looking at the same portrait anymore. The face has been so abstracted and it’s so far removed. It brings the viewer closer into the image to study it further. All the features are there, they’re just morphed and turned into something else.

So what happens when you have the photograph in front of you?

Every rip and tear is intuitive and organic. Sometimes I’ll take an object in the photograph and follow the outline of it to create a new shape that you see in the completed work. Other times I’ll sandwich images and tear them together. My favorite thing is to tear the corner and emphasize the small amount of information in that work.

For me it’s the process that basically tells me I'm finished. If I rip an image once and it’s the only copy I have, then it’s done (laughs). I can’t go back. Well, I could go back, but I don’t like working backwards and restarting again. If the completed work doesn’t look interesting or if it’s a shape that I’ve kind of shown or a tear I’ve done multiple times, I will keep going with whatever is left of the image.

Sometimes I don’t really see the end. If I keep going and it doesn’t look good, then I’ve kind of screwed up that artwork, and I’ll move on to the next.

Do you ever feel bombarded by how many photographs there are and how many images we are all producing in this cultural moment?

It’s totally overwhelming.

The first bulk of images I bought was at a flea market in Los Angeles in 2016. This guy had a booth situated with bins and bins of photographs. I was sifting through them, trying to pick out the best ones, but was stressed out by how many there were. There were so many images I wanted and I knew I couldn’t have them all. An image was 25 cents to one dollar, and I thought that was too expensive, especially for a little handful. I thought about getting a huge random bulk, and not selecting them individually. So I just picked three bins and threw him a dollar amount to see if he’d take it. I don't think he had someone so bold as to ask like that. I ended up with a steal and a trash bag worth of images.

The digital world and the media gives us limitless access to images. How has the digital age influenced your work, since you work so closely with the photograph?

I became bored with the digital aspect of photography. Digital is immediate, and I felt like I didn’t need to add more images into the world. I lost motivation to work on specific projects. I wanted to start working with what was already out there in the world. When I started looking at analog photographs, the parameters were already created for me. The images had been taken, and it was then up to me to utilize what images I wanted and how I wanted to reimagine them.

I am interested in seeing these photographs as the sole copy. These photographs are the only ones that will ever exist, and I want to see what I can do with that. Digitally archived images often destroy that aspect of photography.

What about the fact that most of us have access to photography with our phones and the ability to share them through social media? Has this influenced your work or your life as an artist?

I guess the presence of social media influences my work or the idea of why I’m still working in this format. Social media is just another turn of the century outlet for something that was practiced years ago when photography first became commercialized and available to a mass market in 1901 with George Eastman and the Kodak Brownie camera.

The amateur or novice image influences my work. I’m blown away by bad composition or erroneous photo practices. Social media is presenting new, sloppy, bizarre aesthetics, and it’s great.

When I think of the images I’m working on, there’s a lot of images that reflect and relate to the images I see on Instagram. For me, social media emphasizes a motive to continue working with analog images or in similar ways.

What was creating the work for the Octopus Initiative like? Can you describe this body of work?

I was conceptualizing for a good two months before I started executing the body of work. I was experimenting and playing around and then I cranked out all of the works using some new ideas, some old.

For some of the works, I started to scan the images, like the portraits or some of the weird, mundane landscapes. I moved away from the actual artifact, something I hadn't really done before. I looked at them more as images rather than objects...looking past the photo material itself.

I started sanding or rubbing the photographs with one another. I wanted to give them a “photo finish” by using photographs as my sanding paper. I created a custom sand desk that I would adhere to a palm sander, then I’d rub two photos together to give it that photo finish.

Was the Octopus Initiative project the first time you used that process of rubbing two photographs together?

Yes! I didn’t know what was going to come out of it, it was definitely an experiment but I knew the concept was there. I posted it on Instagram, jokingly showing off what I was doing in the studio, and it was really funny to see people’s responses. So many people were like “what are you doing, that’s so funny!” or “that’s so weird”, “that’s so Duchamp”. I was taken aback that people found it hilarious (laughs). So I kept going to see where it would go.

Are the works a series, or were they intended to exist together?

Any of the images I sand are a series and will fall into that category of “rubbings”. The works that I sanded are really apparent. They’re the ones that look sun flared, orange, red, and a little faded. But truthfully, I don’t think I ever see my work as a series. Sure, the aesthetics are the same and they’re all appropriated images, but every work is unique in my eyes.

What do you think the importance is in living with artwork?

I think people should gravitate towards images or works of artwork they find pleasing and I think it’s very important to support local artists. If you know an artist—local or not—that makes interesting work, have a conversation.

It’s also important to break out of your comfort zone. I think there’s a line people are afraid to cross. People should be confident in liking what they like and should know it’s okay to buy artwork and own a work of art. I don’t think that’s a practice people have learned.

Art isn’t just a strictly visual thing that acts as eye candy in your house...it can totally spark a conversation. That’s what’s really important about having artwork in your home.

Last question. What has been one of the hardest things about being an artist, and what has been one of the most rewarding things?

I moved to Denver in 2015 and in the last four years, it has been really amazing to see so many artists change, grow, and move in different directions. It has also been sad to see some of them go, it’s bittersweet.

There are a lot of hard things about being an artist, like being present in the social scene and making a living wage, especially as an emerging artist in a city where rent costs are squeezing every penny out of people's pockets. It’s a hard space to navigate and continue making work in. There’s self-doubt and you wonder if you’re going in the right direction.

The Octopus Initiative was a really big success for me. That project helped solidify my motives in being an artist and everything I’ve worked on and with in my career in the past. Hard work pays off eventually, it's the eventually that can be the hardest part.