Art

November 26, 2018

Chris Oatey on making maps, his infatuation with carbon paper, and capturing a fleeting moment

Our next featured artist is Chris Oatey. We visited his beautiful brick home on a street lined with lush trees. He met us outside, informing us that we were some of the first people to see his new studio space in his basement. His studio highlights his artwork well: the white walls and wooden floors complement the primarily monochromatic works perfectly. We sat down, La Croix drinks in hand, and talked about his history as a map maker, his obsession with carbon paper, and how he captures fleeting, intangible moments.

Oatey answered our questions with transparency and a gentle manner. We sifted through works of different media, from smaller drawings created during turbulence on a plane, to larger sculptural objects made out of crumpled carbon paper.

You studied cartography in your undergraduate program and your work often suggests a narrative about landscape, the border, and the movement of people, amongst many things; how did you become interested in these topics?

So, I went to CU Boulder and was a geography major and cartography minor. I ended up in geography because I was interested in how borders were created and the movement of peoples over time. I think geography is essentially the study of the world. From there, I was always drawn to landscape and how maps are made, and I chose cartography because of my interest in how to represent spaces. There’s something about the way maps are made that translates to the way I work now. There are different levels in map making that compare to levels of specificity in the art world. In map making you call it “generalization.”

When you’re going to start something like cartography you think there is also an adventure aspect to it. But, what ended up happening was that it was just me in a dark room clicking a mouse, refining layers, making actual maps, printing them out, and then scoring and folding them—which was cool, but there was a limit to it.

Were you practicing your art at this point in time as well?

My mom is an artist, and from a pretty early age I was exposed to art, but I never really thought it would be a career for me.

I went to Otis College of Art and Design in Los Angeles for grad school, and that was sort of the first time I said I wanted to take this seriously. So, I was different than a lot of people, who held undergraduate art degrees before going getting an MFA. I was always making art on the side but had never taken that leap to where I wanted to put myself out there in that way.

So when did you take that leap? Did it happen intentionally, or was it a slower development over time?

That is a good question. When I was living in San Francisco, I had been working in education for a while at a bilingual elementary school, and was doing a lot of things around language. I had been doing projects on the side, but it became clear to me that I wanted to go to grad school to get caught up on contemporary art discourse and insert myself where I could.

You’ve talked about how you got interested in map making. How does map making influence your art, if at all?

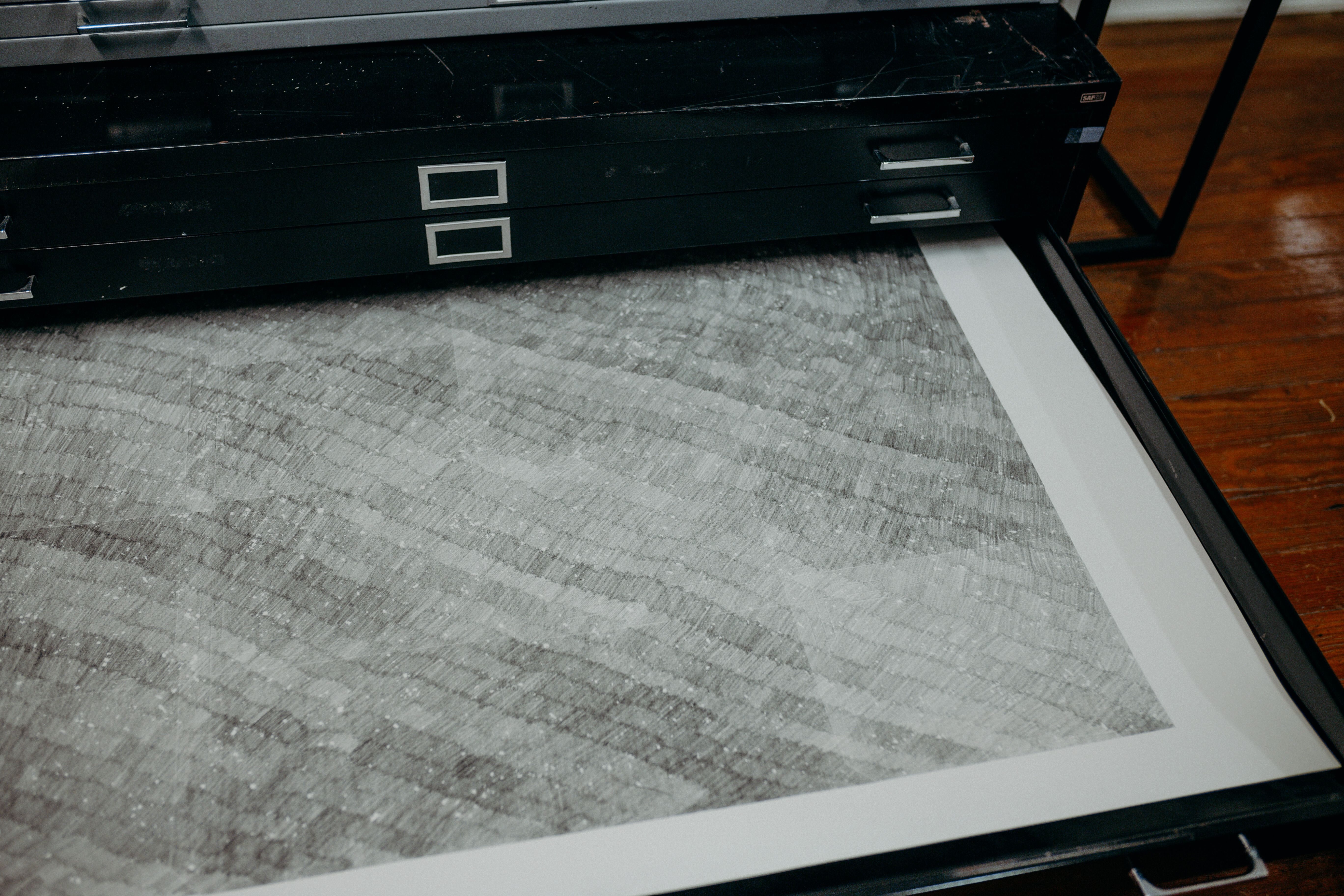

The process that I am using now involves carbon paper. I use smaller sheets of carbon paper to make larger carbon templates. That is a layer that I will draw through with an image printed out on top of it, sometimes using multiple images. Other times, I repurpose the carbon paper over and over so the images that are set from the previous drawings are carried over to subsequent ones.

That physical process of transferring one thing to another is directly related to map making. What I am really interested in it is the ability to have your hand be evident in a very subtle way.

Paper seems to be the main material that you work with. What is it about paper and its properties that intrigues you?

I started using carbon paper about 10 years ago. This was when I was trying to figure out just how to make an image, and [was] trying to fit myself into my preconceived idea of what a painting or drawing was supposed to look like. I started experimenting with different materials and what was great about carbon paper was that once I started using it, I never had to think about the medium I was going to use.

In providing that limitation to myself it has actually expanded the possibilities for me. I have taken it on to see how many different ways can I make a drawing with carbon.

Is carbon paper easy to find? Do you see yourself continuing to work with the material?

It used to be (laughs). Maybe a year or two ago I was starting to see that carbon paper was getting more expensive, so I just bought a ton of it. I probably have most of the carbon paper on planet earth now (laughs).

I didn't want to lock myself in. It’s not like I have to keep using carbon paper but I also didn’t want the fact that I couldn’t find it to make me change mediums. I don’t think that I’ll stick with it forever.

But you could if you wanted to because you have all of it! Can you tell us a little bit more about your artworks in the Octopus Initiative, what is the series?

It was important for me to make that whole body based off the same subject. They’re all engravings that originated as part of the Mexican Boundary Survey, when they were trying to figure out where the U.S.-Mexican border would be in the 19th century. There was a whole process, starting with surveyors that would go out and make sketches, from those sketches there was another drawing made, and there were print studios that made the actual engravings that were part of the survey. At that point nobody knew what the landscape looked like. I have the set of books where the imagery originates from.

They start on a very small scale. I blow them up, unearth the smaller details, and continue the initial process of surveying. Some of them were named after how the final form looked, but all of them have a connection back to the subject matter.

And how did you become interested in that topic?

When I was in Los Angeles, I abandoned earlier ideas I had for work addressing borders. I had really good intentions, but I just felt like it was a roadblock to have such a weighty subject matter. I’ve now found a way to be comfortable with it in this context.

Two of the other prints that I’ve used have been hanging in our house for about ten years. It didn’t really sink in that these were such a good pairing with my current working methods. One day it clicked with those always being in such close proximity.

When you finish a work, does the work change at all from what you initially imagined?

It varies depending on what the subject is or the way that I made it. Maybe this happens to any artist—you sort of wonder what’s the worth of what you’re making. But something that has been consistent in using the carbon paper is that at the end of making one of them, it always ends up being worth it.

Every time I finish a work, I relearn why I am doing this process. There’s something about infusing the subject matter with work, thought, and care. The whole point is for someone else to come to it and do the same thing.

We live in an increasingly paperless age...has the digital world changed things for you?

There is an ease at which you can acquire imagery to use. I value artwork where there is a certain amount of time taken, and work that goes into it. I am invested in the human elements involved in creating things.

I use the same type of paper, and the same type of carbon. The process has changed and I often think how I could open up my process, but don’t want to feel like I have to. I also don’t want my infatuation with the quality of the mark that is made using carbon to limit what I can do.

Is there anyone else that is doing what you’re doing with carbon paper? Who or what inspires your work?

Using carbon paper…maybe not. There are certain artists and artist’s projects that I am interested in. I can’t remember who said this, but someone said that any time you are about ready to finish a body of work you need to go back and look at everything you’ve done up until that point in order to be ready to do the next thing. You can’t just simply finish something and go on to the next thing.

Dogs Chasing My Car by John Divola is one work that consistently inspires me. He was out in the desert and there were dogs chasing his car and he decided to mount a camera to the side of his car and take photographs of them while driving. There’s something sort of fleeting about that moment, that relates to some of my work and some of it not, too. There is something that the artist is after to highlight a moment. Through trying to represent what, say melting snow would look like, you are creating something that almost doesn’t exist in the thing you are trying to represent.

I am interested in the sublime. Vija Celmins is an artist I think about, also Dieter Roth and his Work Tables/Tischmatten, Sigmar Polke’s copier drawings, and On Kawara with his meditations of time and space. Like looking out into the ocean and trying to rationalize your position with respect to different views or things that are happening. There is a series I worked on for at least eight years of turbulence drawings, which I did when I was on an airplane. I was trying to keep my pen on the paper and not influence it, and let the turbulence do the drawing. There was something there too, in trying to measure the intangible.